As the year draws to a close, what are the economic takeaways?

Global rate of exploitation increases

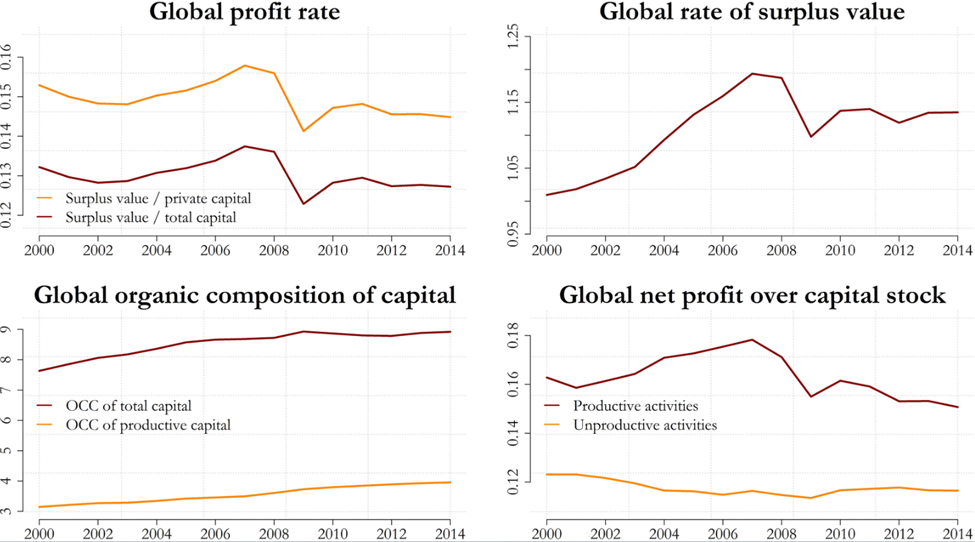

The first big news: Marx is right. Some of us always knew it, but this year Tomás Rotta and Rishabh Kumar published in Structural Change and Economic Dynamic their research based on the study of 43 major economies in the 2000–2014 period. Their research shows that, consistent with Marx’s hypotheses, the average profit rate declines at the world level, between countries, and within countries. The global rate of exploitation increases until 2008 but stagnates after the financial crisis, while capital intensity continued to increase. Rotta and Kumar’s research investigates three fundamental claims at the center of Marx’s economic theory. First, that the origin of value in capitalist societies is productive human labor. Second, that capitalist profit originates from surplus value through the exploitation of labor, which is the appropriation of unpaid labor time in productive economic activities. And, third, that competition forces companies to adopt capital-intensive labor-saving techniques of production. From these three fundamental claims, Marx predicted that economic development would be marked by technological advancement and by capital intensity rising faster than the rise in the rate of exploitation, leading to a long-term decline in the average rate of profit.

The importance of these findings should be understood in the context of Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit under capitalism. Because of the capitalist competition, growing automation of production, and (as Rotta and Kumar show) decreasing share of productive activities, the rate of profit under capitalism has a general tendency to fall in the long run. As a result, unemployment increases, the bargaining power of workers over their wages decreases, exploitation intensifies, and the suffering of the working people deteriorates beyond the point where it can be tolerated. As Marx thought, this tendency represents a mechanism that contributes to the self-destruction of capitalism and ultimately causes a socialist revolution.

It is premature to count the remaining days of capitalism, which throughout its history has shown a remarkable capacity for adaptation. But the data shows that the key contradiction of capitalism, the contradiction between labor and capital is not disappearing or transforming into “mutually beneficial cooperation”. The future of capitalism will be defined by a growing rate of exploitation, social conflicts, and class struggle. Will this contradiction be resolved by a socialist revolution? If Marx was right about the falling rate of profit and a growing rate of exploitation under capitalism, was he also not right about how capitalism will end? Let us not forget that Immanuel Wallerstein predicted the collapse of the present system of capitalism by 2030-2050. According to him, at that time, a great disturbance will put an end to five centuries of modernity, and a more egalitarian form of social organization will arise.

Profit is the king and the failure of sanctions

The events of this year have also confirmed yet another Marxist insight: in a situation of a secular decline in the rate of profit, capitalists would do anything to mitigate this trend. In Das Capital, Marx quotes an economist who says that if capital can get 100 percent profit, it will “trample on all human laws; 300 percent, and there is not a crime at which it will scruple, nor a risk it will not run…If turbulence and strife will bring a profit, it will freely encourage both.” The evolution of the sanction regime against Russia is a perfect illustration of this statement. Everyone agrees that the sanction regime isn’t working as effectively as it was designed to. Russia’s economy has indeed proven to be more resilient than many expected. A combination of (regressive) export substitution, growing military production, and a prudent fiscal policy has resulted in the growth of Russia’s economy in 2023 by 2-3%.

But a major reason that keeps Russia’s economy afloat is sanctions evasion. It takes two to tango, the same as to evade sanctions. Pushed to the wall by the falling rate of profit and sensing super profits due to discounts on Russian exports (such as oil and its derivatives), capitalists around the world happily engage in sanctions evasion. As supply chains lengthen and involve more intermediaries, Russian imports have also become more attractive. Western sanctions imposed over Russia’s invasion have had a temporary impact. Moscow and its helpers have largely succeeded in reconfiguring supply chains — with the help of China, Hong Kong, and countries in Russia’s backyard like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and NATO member Turkey. Russian imports of microelectronics, wireless and satellite navigation systems, and other critical parts subject to sanctions have recovered to near pre-war levels with a monthly run rate of $900 million in the first nine months of this year. This year, Russia has maintained its oil exports at the 2022 level (over 242 million metric tons) and has succeeded in selling almost all of it well above a Western-imposed price cap of $60 per barrel.

Under capitalism, profit is the king. Government regulation (including the price cap on Russian oil) is possible only to the extent that it does not seriously conflict with private profits. When it does, such regulation is ignored, evaded, or otherwise made irrelevant. As Adam Smith quipped, whenever capitalists get together, the only thing they want to discuss is how to swindle the public out of their money.

Serbia: election protests and capitalist competition

In Serbia, the opposition launched street protests over the 17 December election, which they claim was stolen from them by the incumbent regime of President Vučić. Is it yet another expression of the social conflict and class struggle mentioned above? It is not. In the West, the protests are presented as the struggle for democracy against tyranny. No one is more interested in genuine democracy than the working class. But viewed from the Marxist perspective, it is a struggle between two groups of capitalists: the “national” bourgeoisie and the “international” bourgeoisie.

In the words of the Ukrainian sociologist Volodymyr Ishchenko, the so-called maidan revolutions (“There will be ‘no new Maidan’ in Serbia,” said Prime Minister Ana Brnabić) are typical contemporary urban civic revolutions. They only temporarily weaken authoritarian rule and empower middle-class civil societies. They do not bring a stronger or more egalitarian political order, nor lasting democratic changes. None of the post-Soviet, so-called maidan revolutions posed an existential threat to the post-Soviet political capitalists as a class by themselves. They only swapped out fractions of the same class in power, and thus only intensified the crisis of political representation to which they were a reaction in the first place. This is why this type of protest has occurred so frequently. Typically, in post-Soviet countries, the maidan revolutions only weakened the state and made local political capitalists more vulnerable to pressure from transnational capital — both directly and indirectly via pro-Western NGOs.

The “international” bourgeoisie behind the current protests hopes to sustain the falling profit rate through two channels: by redistributing the insider rent within the existing framework of political capitalism in their favor and by securing better access to international financial markets and goods markets. Highlighting their readiness to cooperate with the West (unlike the “national” bourgeoisie currently in power), this group of capitalists counts on securing better deals in terms of access to cheaper capital and preferential access to European markets with a higher market premium. Regardless of the outcome (as I write this, things are still in flux), no lasting positive change for the working class can be expected.

Gaza: Politics cannot but have dominance over economics

The war in Gaza demonstrates a well-known Marxist thesis that “the economy matters only in the last instance”. In the words of Friedrich Engels, the economic situation is the base, but the different parts of the structure – the political forms of the class struggle and its results, the constitutions established by the victorious class after the battle is won, forms of law and even the reflections of all these real struggles in the brains of the participants, political theories, juridical, philosophical, religious opinions, and their further development into dogmatic systems – all this exercises also its influence on the development of the historical struggles and in cases determines their form. It is under the mutual influence of all these factors that the economical movement is ultimately carried out. Vladimir Lenin was even more outright: “Politics cannot but have dominance over economics. To argue otherwise is to forget the ABC of Marxism.”

Gaza’s Hamas faced a crisis of legitimacy in Gaza (let alone beyond its borders) before it attacked Israel on 7 October. The group established a brutal dictatorship and has not held elections in 17 years. It routinely restricts the rights of disadvantaged and minority groups, such as women and LGBT+ community (this is why the expressions of support for Hamas’s slogan “Palestine from the river to the sea” coming from feminist and LGBT groups are so ridiculous).

Built into a regime of political capitalism tightly (and if needed, murderously) controlled by Hamas, the local bourgeoisie has seen declining rates of profit for some time. It badly needed a solution. In a situation when real GDP per capita shrank by 27% between 2006 and 2022, and when 56% of the population live below the poverty line, any further increase in exploitation is impossible. But rather than a more conciliatory stance that could bring new benefits in terms of international support and cooperation with Israel, Hamas opted for an armed attack, trying to wrestle at least some benefits using hostages as leverage. An impartial observer would think that this decision was against the longer-term interests of the Gazan bourgeoisie (an exchange of hostages, however beneficial, could create only short-term benefits). However, a toxic mix of ideology and religious fanaticism precluded a more optimal solution. The havoc wreaked by Hamas on Gazans does have an economic foundation but was caused by a particular political decision. Adam Tooze argues in his recent piece in Financial Times that economic growth does not necessarily build peace and cooperation. It appears that the same is true for underdevelopment (or de-development as the economic process in Gaza is often referred to).

By way of conclusion

Conceptually related to the dynamic between the economic and political, are the findings from my recent research on urban economic and financial resilience during COVID-19. Carried out on a sample of 16 cities around the world, the study shows no correlation between the wealth of a city (measured as its Gross Regional Product) and the COVID-19 impact (measured as a loss in own source revenues). And this is a very encouraging funding. Even not-so-well-to-do cities may build resilient socio-economic systems minimizing the adverse impact of economic shocks. Politics does matter.

Marx was right.