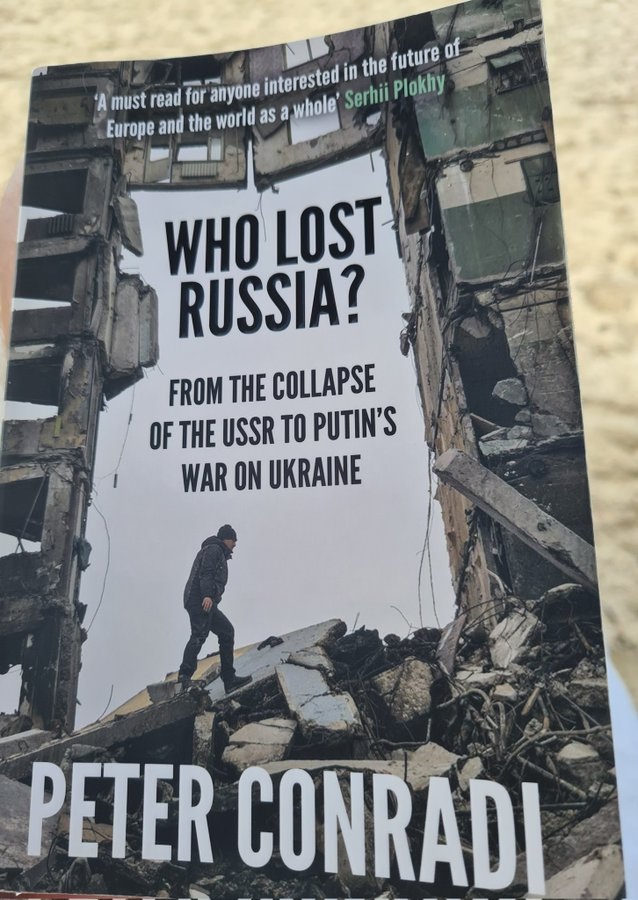

Who Lost Russia is a revised and updated edition of a book that was originally published in 2017 and was prompted, as its author Peter Conradi informs us, by Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the war in eastern Ukraine and the geopolitical crisis that followed. Back then the author wanted to take a longer look at Russia and its relationships with the West to understand how it became possible. The new edition covers the events up to 2022 and the beginning of the Russian attack of Ukraine but there have been no changes to the earlier chapters or to the book central argument, which, in the author’s opinion, has held up well.

But what is the central argument? It’s not easy to answer this question as the author rarely becomes judgmental, and his own position is hardly discernible behind the myriad of events of the past 30 years that he meticulously chronicles. The approach is in line with the best journalism practices, but this lack of a specific perspective and analytics is somewhat disappointing as it makes the reader guess until the very end about the author’s central argument, which comes in the last pages of the book:

“Looking back over the past three decades, it is difficult to pinpoint the moment at which relations between Russia and the West went wrong. In fact, it may be there was never a time that they really went right. Misunderstanding on both sides were rife – and had their roots in an inability to agree on what happened in 1991 and the tendency to conflate the end of the Cold War, the collapse of communism and the breakup of the Soviet Union.”

As for Ukraine, Conradi subscribes to the view that the battle over the future of Ukraine was not so much the cause of the breakdown in the relationship between Russia and the West as it was its consequence, harking back to the central argument. The West could not appreciate Russia’s security concerns over NATO’s expansion and the criticality of a friendly (or at least neutral) Ukraine to the post-Soviet Russia project whereas Russia’s politics were increasingly driven by revanchist and anti-Western sentiments.

There is not much that Conradi has to say about economics and its links with political developments. But he correctly identifies the botched economic transition and notoriously corrupt privatization program of the early 1990s as a mighty blow that undermined Russians’ trust in Western-style democracy. Furthermore, this laid the foundations of Russia’s present-day crony capitalism with its oligarchic characteristic. Conradi mentions Ukraine’s transition and capitalist development only in passing but it was no less painful (and no less oligarchic) than in Russia. Deprived of Russia’s commodity boon, de-industrialized and simplified in economic terms, Ukraine’s predicament was even worse that Russia’s. The gap between the two countries continued to widen during the post-Soviet period as Ukraine plunged from about 50% of the Russian GDP per capita in 1989 to about 25% in 2013.

An interesting question that emerges in this context (but that is not explored by Conradi) is why similar experiences and situations produced very different political outcomes. It would appear that Western-style democracy was discredited in both countries to the same extent. In fact, given Ukraine’s economic woes, one could expect that Ukrainians would be even less enamored with democracy and its professed benefits. The reality, however, was very different for the two countries: Ukraine has continued its journey to democracy (however imperfect) whereas Russia has drifted to a more authoritarian and repressive regime.

This review is not an appropriate place to discuss this issue at length, let alone provide answers. But I tend to agree with Volodymyr Ishchenko (https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7788) that in the competition between the two Ukrainian capitalist factions the one that took an accommodationist strategy towards the transnational capital has ultimately prevailed over the faction of political capitalists that chose an openly confrontationist position against the threat of the transnational capital. This accommodationist strategy implied certain concessions and a pro-democratic posture, even if token in many cases. At the same time, by selling themselves as indispensable figures in fighting against Putin, the first group hopes to secure some ease for them on the “anti-corruption” agenda promoted by the West and retain their political and economic influence. However the big capital in Ukraine may be (in)sincere about its democratic leanings (and capital and democracy are not natural bedfellows), this accommodating strategy did influence the public opinion and behavior, leading to greater openness and more inclusive political space.

The other possible economic explanation (often overlooked) is that, despite their economic difficulties, Ukrainians may have been less disappointed because of a significantly lower inequality. It is an established fact that income inequality is perceived through a comparison with the other income groups, and it is the relative differential that matters. Despite higher incomes, Russia’s Gini index jumped to about 40 in the late 1990s-early 2000s whereas Ukraine’s even decreased to about 25 at the same time from about 30 in 1991. “New Russians” as they were known in Russia, were a source of strong social indignation due to their obscene newly acquired wealth and “conspicuous consumption”, to borrow from Veblen.

The Gini index, being a summary measure of inequality is known for its low sensitivity to the changes at the tales of the income distribution. As a result, the Gini index tends to be most sensitive to transfers around the middle of the distribution and the least sensitive to transfers among the very rich and very poor. Hence, it is useful to analyze the income distribution in the two countries, which makes the income diversion between them even clearer. Whereas the share of the richest 10% in Russia jumped from 40% to 50% in the early 1990s and has remained there since then, the share of richest 10% in Ukraine saw there share declining from 40% to 30%. The result is that the poorest 50% of Russians are 1.5 times poorer than the poorest 50% of Ukrainians. Non-income factors may have also played a larger role in Ukraine in absorbing economic shock due to a more developed public infrastructure and utilities, which the country inherited from the Soviet Union.

Another economic point that Conradi makes is linking Russia’s renewed assertiveness in domestic and international affairs in the 2000s with oil revenues. This is of course a very common argument, almost as common as that the collapse of the Soviet Union was caused by the collapsing oil prices in line with McCain’s characterization of Russia as “a gas station masquerading as a country”. No doubt that oil and gas revenue play an important role but it should also be remembered that the oil and gas industry accounts for about 20% of Russia’s GDP although Russia typically depends on oil and gas sales for around 45% of its budget revenues. Other factors, which should not be disregarded, were also at play, such as improved law enforcement, increased foreign direct investments, and tentative attempts to promote value adding economic activities. Anyway, whereas the correlation between GDP per capita and the price of crude oil is quite strong, there is no correlation between the oil rent and GDP per capita.

Conradi justly notes the de-industrialization and reduced economic complexity in both Russia and Ukraine as they became exposed to external markets where their industrial production was non-competitive. In Ukraine, the situation was exacerbated by the loss of its industrially developed areas in eastern Ukraine. Russia’s failure to develop its high technology sector through Skolkovo Innovation Center is also duly mentioned. The share of high-tech and science-intensive industries in Russia’s GDP increased by a paltry 1% over the decade until 2022, and oil, gas and coal accounted for almost 70% of all Russian exports in 2021. However, this reversion of development is characteristic of not only Russia and Ukraine but many other developing countries, such as Brazil and Mexico (for an excellent overview of this trend, see The Long, Slow Death of Global Development by David Oks and Henry Williams at https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2022/11/the-long-slow-death-of-global-development/#notes).

Conradi concludes by saying that despite all attempts to “cancel” Russia, it’s just too big to be cancelled. America and Europe will have to find a way of working constructively with Russia as it cannot be allowed to remain an angry, brooding presence that casts a long shadow over the Eurasian continent. He recognizes though that the East-West tensions that grew during Putin’s presidency is not a “Putin problem” that will disappear when he eventually leaves the Kremlin. Russia’s size, imperial past and military make it unlikely it will ever be content to be a junior member of anyone else’s alliance (although we’re yet to see how its relationship with China will develop). But, in his opinion, Russia itself must also change and shed its imperial mindset. Only then will Russia and the West be able to find each other again. This sounds like a fair assessment, except that for now we don’t know when and on what conditions this rediscovery may happen.

Do I recommend the book? Yes, if you need a refresher on Russia’s past 30 years and want to pass a couple of evenings over a page-turner that reads almost like a political thriller. But don’t harbor any high expectations.