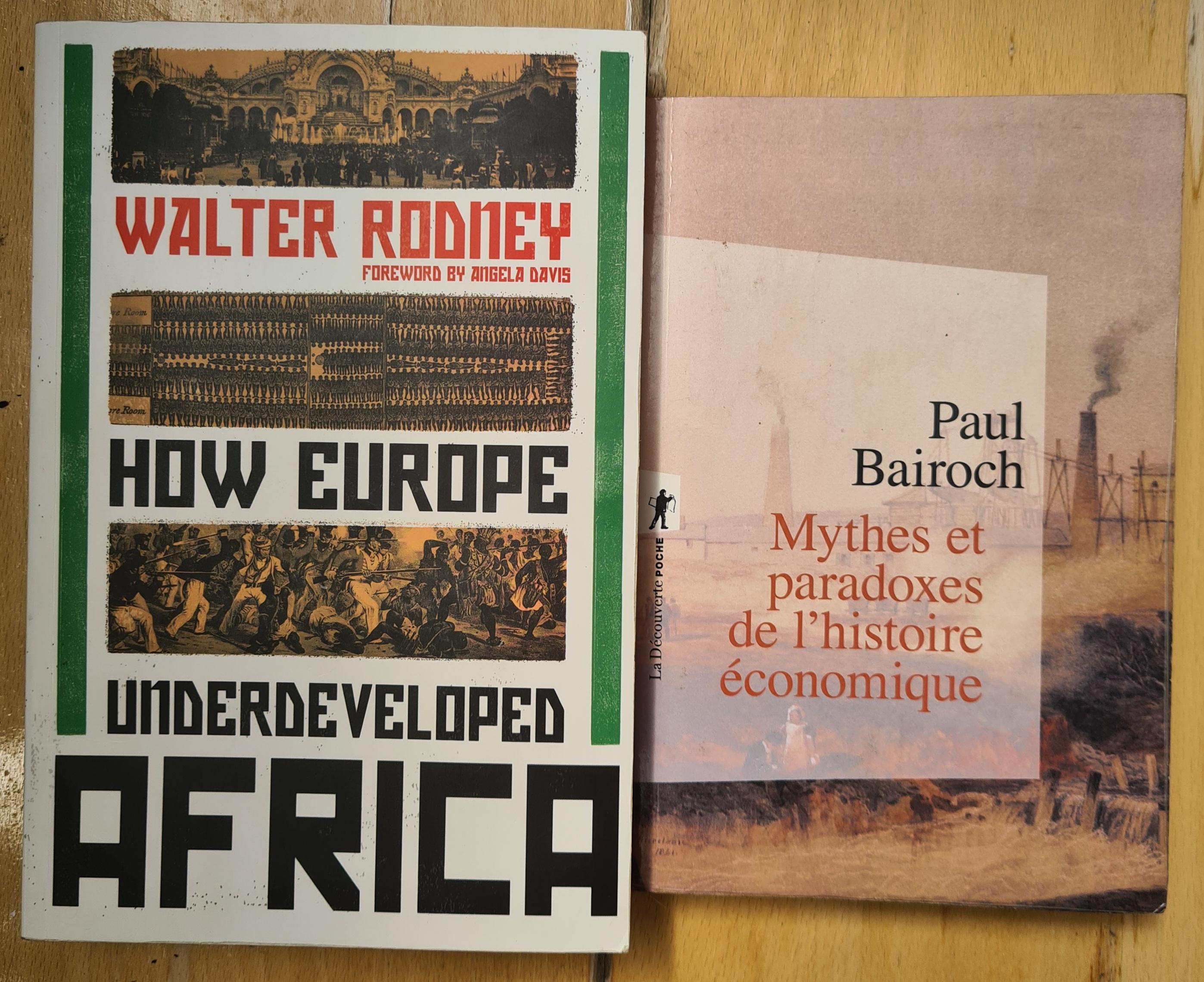

This is not a real review; rather this is a homage to two great, but very different books, written 20 years apart: Walter Rodney’s How West Underdeveloped Africa published in 1972 and Paul Bairoch’s Mythes et paradoxes de l’histoire economique published in 1993. The actual time space is actually less: Bairoch’s books summarizes his research starting from the 1960’s; Rodney was assassinated in Guyana in 1980 at the age of 38 and did not enjoy the privilege of a ripe age to summarize decades of academic work.

Both authors were academics but of a very different type. Bairoch was a typical expert economist who spent most of his professional life at the University of Geneva and as economic adviser to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and to other international organizations. Rodney was a prominent Pan-Africanist and Marxist, and was important in the Black Power movement in the Caribbean and North America. He was ready to pay (and did pay) dearly for his political activism with his academic career. He was declared persona non grata in Jamaica in 1968 and banned from ever returning to the country, resulting in his subsequent dismissal by the University of the West Indies. After three academically productive years at the University of Dar es Salaam, he returned to his home Guyana in 1974. Rodney was promised a professorship at the University of Guyana in Georgetown but the government rescinded the offer when Rodney arrived in Guyana. It is widely believed that his death in 1993 was orchestrated by the Guyanese government.

The two books are as different as their authors in approach and style. How West Underdeveloped Africa is written in the tradition of Marxist pamphlets designed to educate and mobilize working masses. It is written in a lucid and colorful style, in a relatively simple language, and, in a true Marxist fashion, is full of polemical remarks about ideological opponents and bourgeois collaborators. He states his position clearly (the title is a testimony to it) and builds his narrative around a few well-articulated theses. To support this narrative, Rodney uses a multitude of concrete and specific facts, but just a limited amount of consolidated statistics. (This approach often results in transformation of the particular into the general, to use a dialectic category, but sometimes it doesn’t.)

Bairoch’s is a proper academic publication, which is grounded in vast statistical material on a global scale. It is somewhat unusual though in approach: Unlike most books on economics, it does not have a single theme. Instead, it focuses on a variety of historical economic phenomena, which the author believes to be myths, rather than established facts (Mythes et paradoxes de l’histoire economique), and re-interprets them by means of economic analysis. The two books use two very different conceptual frameworks. For Bairoch, there exist no “laws” or rules in economics which are valid for all periods of history or for every economic system. Rodney, as a Marxist, believes in a linear development process where one socio-economic formation replaces the previous based on a more advanced mode of production.

Furthermore, Rodney’s book is openly partial, anti-capitalist first and anti-colonialist second. Bairoch’s is outwardly impartial and sterile as befits an academic publication. It’s possible to agree or disagree with Bairoch; it’s impossible not to experience strong feelings and remain emotionless when reading Rodney.

Nevertheless, the two books meet at the point where they discuss the socio-economic effects of colonialism, from the perspective of both the colonies and metropoles. For Rodney, this is the focus of his book; for Bairoch, this accounts for about one half of his book. (Relations between industrialized and developing countries was a persistent theme in Baroch’s work. His magisterial opus “Victiores et deboires” describing the global economic and social history from the 16th century until the end of the 20th, has a chapter called “Africa: from slave trade to economic exploitation”.) Interestingly, both books raise the same key questions about colonialism and development, sometimes agreeing and at many other times disagreeing about the answers in a kind of an absentee dispute divided not only by distance by also by space. The key questions that both books explore are What was the contribution of colonialism to the development of the West? Did colonialism play a decisive role in the industrial revolution? What are the effects of colonialism on developing economies? What are the costs and benefits?

These questions are as topical today as they were 50 or 30 years ago. The contribution of colonialism to Western development and non-Western underdevelopment is one of the themes researched in Peter Vries’s Escaping Poverty published in 2013. One of the most recent works on this topic published in 2020, The Economic History of Colonialism by Leigh Gardner and Tirthankar Roy of Bristol University, investigates the same issues.

Both books agree about the overall negative effect produced by colonialism on the economies of colonial countries. As Bairoch notes: “The origin of the numerous negative structural characteristics of the process of underdevelopment goes back to the European colonization.” He highlights two factors in particular: orientation towards production of raw materials required by European industries (primary products accounted for 90% of exports from the [future] developing world in 1815-1914), and rapid de-industrialization of colonies due to more competitive Western products, which flooded local markets. Rodney fully agrees: In his opinion, the natural path of African development was arrested with the arrival of Europeans, locking African economies into backward production modes at a very low technological level designed to service European economies, which created the entire added value using raw materials produced by Africans. African economies were thus channeled not in the direction that would benefit those countries or the continent most, but in the direction that would benefit their respective metropoles. The pre-colonial relations of exchange between various African areas based on their competitive advantage had been destroyed and replaced with (unequal) relations of exchange with metropoles.

But Rodney goes beyond only the structural impact of colonialism on African economies. In his opinion, colonialism undermined the historically necessary evolution of the relations of production in Africa. Rather than progressing towards higher socio-economic formations (as Europe did), Africa ended up with an ugly hybrid system that brings together the worst of the two worlds. According to Rodney, an economy must register advances which in turn will promote further progress. However, to be held back at one stage means that it is impossible to go on to a further stage. Rodney argues that the European slave trade was a direct block, removing millions of youth and young adults who are the human agents from whom inventiveness springs. Those who remained in areas badly hit by slave capturing were preoccupied about their freedom rather than with improvements in production. “What Africa experienced in the early centuries of trade was precisely a loss of development opportunity, and this is of the greatest importance.”

From this point on the two books diverge conceptually on the relations between the developed and developing world during the post-colonial period. Rodney believes these relations are locked in a neocolonialist center-periphery pattern. In the world governed by the capitalist mode of production, and unequal trade relations, “development of some means underdevelopment for others”. To Rodney, colonialism (and is extension in the form of neo-colonialism) is not merely a system of exploitation, but one whose essential purpose is to repatriate the profits to the so-called mother country. From an African viewpoint, that amounts to consistent expatriation of surplus produced by African labor out of African resources. It meant the development of Europe as part of the same dialectical process in which Africa was underdeveloped.

Although he doesn’t call globalization by its name (the term didn’t exist 50 years ago), Rodney is keenly aware of the international division of labor, which he believes to be skewed in favor of the West and to the disadvantage of African countries. He believes that this unequal relationship is reflected in the secular decline of the terms of trade for developing countries in line with the Singer-Prebisch theory.

Bairoch, on the contrary, “exposes” the secular decline as a myth. He states that the terms of trade for developing countries were steadily improving between 1965 and 1984, with some decline from there until 1991 due to increase in oil prices. However, his research shows that this improvement was achieved mostly due to oil exporting countries as the demand for oil boomed during the post-war period. For non-oil exporting countries, the terms of trade stagnated during this period, and dropped by 20% below the 1950 level in 1991. Hence, Bairoch’s claims are not very convincing. There is a vast literature on this issue, with results differing by period and by country. Most research indicates either stagnation or deterioration in the terms of trade over the long period.

This is not surprising if we consider the continued reliance of developing countries on exports of raw materials/primary goods and imports of technologically advanced (and not so advanced) goods from the developing world. Rodney argues that Western colonization (including the post-colonial period) led to what can be called “technological arrest” or stagnation, and in some instances actual regression, since people forgot even the simple techniques of their forefathers. Rodney lists many historical examples when (post)colonialists intentionally denied access to education and technologies to colonized Africans, condemning them to mere subsistence.

The two books diverge further in their assessment of the contributions of slave trade and colonialism to Western development. Bairoch famously quipped: “L’occident n’avait pas besoin du tiers monde, ce qui est une bonne nouvelle pour le tiers monde.” (“The West didn’t need the third world, which is good news for the third world.”) His point is that the slave trade and colonialism didn’t make any noticeable contribution to the industrial revolution or capitalist development in the West, which is good news for the developing world since it implies that developing countries can make progress without the exploitation of other regions. Bairoch argues that, in the early stages of capitalist development, Western countries were largely self-sufficient in terms of raw materials required for powering the industrial revolution, such as fuels (primarily coal and petroleum) and metals. For example, Europe was still self-sufficient in fuels as recently as 1901, exporting more coal and petroleum than importing. Similarly, on the eve of World War I, the developed world was 98% self-sufficient in metals and 87% in cotton and wool.

Rodney disagrees on two accounts. He points out that, for example, 50% of cotton used by Europe was produced in the United States, more specifically in its southern states, and even more specifically on slave plantations toiled by African slaves. For Rodney, Europe’s self-sufficiency is a myth, and its development was greatly helped by the continuous extraction of surplus value from Africa. In addition, Rodney highlights participation of Africans on the side of their colonial masters in international conflicts in Africa and beyond, during both world wars. In that respect, metropoles benefitted through colonial contributions to the war effort. During both world wars, metropolitan countries relied on their colonies for supplies of both manpower and commodities which, although quantitatively not always a large share of wartime mobilization, could be strategically important during periods when other supplies of commodities were restricted.

But Rodney takes a broader view of the benefits received by the Western world. It’s not only the trade and access to resources, but also first and foremost the overall stimulating impact of colonialism in various areas, from manufacturing to urbanization. This is what he says about it: “The most spectacular feature in Europe which was connected with African trade was the rise of seaport towns dash notably, Bristol, Liverpool, Nantes, Bordeaux, and Seville. Directly or indirectly connected to those ports, there often emerged the manufacturing centers which gave rise to the industrial revolution. In England, it was the county of Lancashire which was the first center of the industrial revolution, and the economic advance in Lancashire depended first of all on the growth of the port of Liverpool through slave trading. In New England, trade with Africa, Europe and the West Indies in slaves and slave-grown products supplied cargo for their merchant marine, stimulated the growth of their shipbuilding industry, built up their towns and their cities, and enabled them to utilize their forests, fisheries, and soil more effectively.”

Before finally disagreeing on the significance of European colonialism in the history of Africa, the two books partially agree on the importance of colonies as outlets for increased capitalist production in the West. In Rodney’s view, African countries were transformed into sales markets for Western industries, contributing to development of Western industries. In doing so, the West, as already discussed, pushed indigenous African goods out of the market) while flooding it with low quality, often outright harmful goods with no (or even negative) contribution to development, such as fire weapons or spirits. This allowed Western capitalists to expand industrial production and create somewhat better conditions for their workers, thus reducing the intensity of the class struggle in the West at the expense of Africans.

Bairoch is less categorical. In his opinion, the importance of colonies as sales market was not the same throughout the period of colonialism and increased significantly only in the early 19th century, with the expansion of colonialism. For example, 53% of the cotton produced in the UK was exported, the bulk of it to the future developing countries, including British colonies. At the beginning of the 20th century, this figure rose to almost 80%. The share of the developing world, Africa in particular, in the structure of Western exports grew during this period from a paltry 2-3% of the total to 14% in 1900. 14% of national industrial production is a significant number by any standards, back then or now, and there is little doubt that what Rodney says (and others, from Marx to Lenin and Rosa Luxembourg had said before him), about the moderating impact of colonial markets on the class struggle in the West in the 19th century, rings true.

The last disagreement point is the relative impact of different colonialisms on Africa’s development. Bairoch contends that colonialism and slavery were an ever-present feature of human development from antiquity. In that sense, European colonialism is not particularly exceptional and cannot be held responsible alone for Africa’s underdevelopment. Furthermore, he points to the Arab colonialism and slave trade, which lasted even longer than the European dominance and resulted in probably twice as many slaves traded during this period (19-20 million compared to about 11 million shipped via the Atlantic route).

Rodney strongly objects to the characterization of slave trade on the Indian Ocean as the “East African Slave Trade” and the “Arab Slave Trade”. In his opinion, it hides the extent to which it was also a European slave trade. Rodney argues that when the slave trade from East Africa was at its height in the 18th century and in the early 19th century, the destination of most captives was the European owned plantation economies of Mauritius, Reunion, and Seychelles—as well as the Americas, via the Cape of Good Hope. Besides, African slavery and slaves in certain Arab countries in the 18th and 19th centuries were all ultimately serving the European capitalist system which set up a demand for slave grown products, such as the cloves grown in Zanzibar under the supervision of Arab masters.

Rodney also strongly disagrees with Bairoch’s statement that European colonialism was nothing special and is remembered only because “it was the last one in a very long series; and it was the last one because the West decided to stop this international trade on a large scale, and it was powerful enough to impose its decision. According to Rodney, the West was guided by ulterior motives disguised as humanitarian concerns. By the middle of the 19th century, the West had realized that non-slave work in Africa proper enabled more surplus extraction. By transplanting slave-like work onto African soil, European imperialism was able to minimize its transaction costs while at the same time boosting the profits.

Both books are very rich, and there is much more in them than has been discussed here. They agree on one major point: Whatever the benefits of colonization, its negative consequences by far outweigh. Even when Bairoch argues that the benefits of colonization were negligible for the West, he is careful to state that this doesn’t imply at all that the costs on the colonies were negligible as well. The exact balance of colonization will never be established and will always be disputed due to lack of data and various methodologies applied. But this is a highly emotional issue to Africans and people of African descent elsewhere in the world.