Two studies in which I recently participated, one on COVID-19 impact on the local government fiscal space and service delivery in Uganda, and the other on the impact of COVID-19 on in African cities triggered my thinking about how we can strengthen the contribution of local governments to COVID-19 response and recovery, including the fiscal dimension of this response.

It is obvious that the fiscal space of local governments is contracting fast under the adverse impact of COVID-19. Part of this contraction is due to the response measures taken by local governments. For example, many local governments have waved or deferred municipal taxes or other charges to help the citizens, particular vulnerable groups, as well as local businesses to withstand the worst moments of COVID-19 and cope with the containment measures introduced by central and local governments. For example, the city of Kampala waived fees and other charges in all markets and facilities under Kampala Capital City Authority for March and April in order to help the traders cope with the growing Covid-19 pandemic. The Cape Town council has announced that commercial property owners will be able to obtain rates relief if they can prove that their business income has been negatively affected by the crisis. Qualifying businesses that fall into arrears may apply to make payment arrangements to pay off the rates over an agreed number of months. No interest will be charged, or debt management actions taken for the duration of the arrangement, provided it is honored.

The estimates of this contraction vary but both my own modeling performed for Ugandan local governments and the model developed by UCLG colleagues for urban local governments in Africa predict a contraction of up to 70% in 2020 (in the worst case scenario). This development is worrisome, particularly as local governments are facing an unprecedented double challenge of preparing for the pandemic while at the same time looking at rebuilding and recovering local economies in the context of partial or complete lifting of the containment measures.

This is a troubling moment. In many countries, and this is particularly true for Africa, the outcome of the COVID-19 situation is far from certain. The number of cases is still on the rise; in fact, the daily rate is even higher than at the beginning of the pandemic. Take Uganda. Back in March-April there were about five confirmed cases daily. In the past two weeks the number of daily cases his risen to 30 but, with a few relatively minor exceptions, the country is more or less back to “normal”. It is true that in Uganda which has recorded zero fatality as well as in a number of other African countries the death toll has been very low but we still cannot be sure about the future developments, given that the virus may mutate or the number of cases requiring treatment (even if the fatality rate remains low) may eventually increase to a level where the local health care system as well as other resources will be overburdened. Against this background, local governments are expected to build up and maintain a certain level of the indigenous healthcare capacity while taking steps for local economic recovery.

This is a clear evidence of the “new normal” unfolding in front of us. Amidst all the discussions about the “new normal” after COVID-19 some fashionable topics such as expansion of digital solutions and the unstoppable march of digital economy in general prevail. But what seems to be almost certain is that the new normal entails living with COVID-19. This implies maintaining a high level of preparedness and an excess capacity of the health care system to treat a large number of patients if necessary while at the same time maintaining the delivery of basic services and rebuilding local economies (hopefully rebuilding them better) in a manner that would minimize the risk of the infection. The other aspect of the new normal (or probably not so new, after all) is an increased role of government (including local governments). A stream of authors, such as Marianna Mazzucato, Joseph Stiglitz, and most recently Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo (https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2020/05/26/abhijit-banerjee-and-esther-duflo-on-how-economies-can-rebound) emphasize the criticality of a strong and able government enjoying a fair amount of legitimacy (regardless of the political system) for quick recovery.

The recent discussions about what can and should be done to expand the fiscal space of local governments to deliver an effective and robust response to COVID-19 focus on three key actions: project, transform, make resilient.

Protecting the local government fiscal space

This refers to near-term activities aiming at, first, protecting the roles and responsibilities of local governments in COVID-19 response and recovery and, secondly, safeguarding an adequate fiscal space for this. It is in this order that that the building of local government fiscal space should proceed in line with the principle “funding follows function”. It is still a case in many African countries that most of local governments’ functions are declarative, not properly resourced and in reality delivered by central government bodies.

The same is true for the current situation. Whereas the role of local governments is officially recognized and appreciated, in practice many central governments deny their independent role viewing them as an extended arm of the central government acting on the latter’s instructions. The only expectation is thus that local governments faithfully fulfil the central government’s orders, nothing less but also disappointedly nothing more. This attitude is killing local initiative, ownership and does not allow the full potential of local governments to be realized. Hence, mutual agreement between the central and local governments and a clear understanding of the deliverables expected from the latter is critical and underlies the measures to safeguard an adequate resource envelope at the local level. After all, in a situation when the COVID-19 response is most often driven from the central level, local governments can deliver only as much as the central government allows them to.

This is particularly true for the recovery phase. Local governments’ responsibilities during the preparation and reponse phase have been relatively clear, defined (albeit narrowly focused on carrying out central government’s instructions) and even somewhat funded as many central governments allocated special grants to enable local governments to perform their assigned functions. There is less clarity about the responsibilities and expected deliverables of local governments during the recovery phase beyond the continued delivery of basic services. Two reasons stand behind this. One is less clarity about the role of local governments and their contribution to COVID-19 recovery in comparison to their roles during preparedness and response which cover mostly health related issues, such as case tracking, isolation, treatment and delivery of essential services. The second reason is more fundamental and is related to the general underdevelopment of the local government economic function. This function requires three well-developed dimensions that enable a meaningful economic function of local governments: institutional (strong and able structures for economic governance), regulatory (enabling regulations to plan, finance and implement local economic development), and financial (financial mechanisms, instruments and adequate fiscal space). With the exception of larger cities (usually capitals), such as Nairobi, Kampala, Johannesburg or Lagos, in most African cities the requisite conditions for delivering the economic function are weak or nonexistent. There is therefore high risk of the central government stepping in and significantly curtailing the role of local governments in post-COVID-19 recovery despite their officially recognized economic functions.

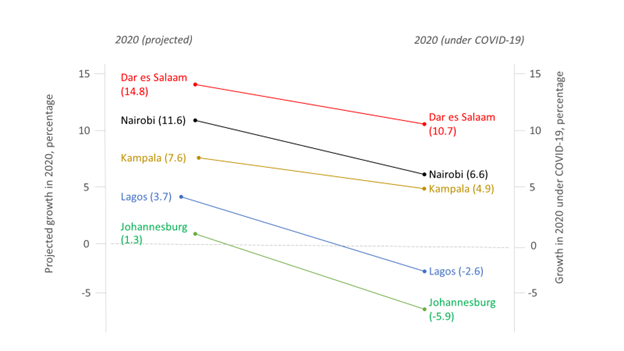

Developing these pre-requisites is a longer-term task although COVID-19 offers an unprecedented opportunity to incorporate the longer-term vision of an economically active local government in the short-term response, test and pilot certain approaches. But for the immediate recovery phase two things are important: (1) to protect their economic functions based on mutually agreed realistic and achievable targets and (2) to protect own revenue space of local governments to ensure a minimum of financial resources for local recovery. The expected drop in OSR will hit particularly hard urban governments (municipalities and town councils), for some of which the OSR losses may amount to about half of their total fiscal space, with large cities registering significant growth drops or even moving into the negative territory. There are two proposals about how local governments can be supported to effectively contribute to post-COVID-19 recovery.

OSR Compensation Fund for local governments. It is suggested that the central government establishes a fund to compensate local governments for the loss of OSR to keep these resources available for the purposes of response and recovery. The Fund will play the same role as the funding facilities currently established for private businesses and SACCOs to inject liquidity to resume their operations. The Fund is designed to preserve local governments’ discretionary fiscal space and enable local economic recovery. The funding allocated for this Fund should come in the form of discretionary grants but it is recommended that the releases from the fund should be subject to approved COVID-19 local reponse and recovery plans to ensure appropriate utilization of the funds.

Local Government Recovery Fund. This is an emergency fund intended to provide short-term liquidity to local governments for local response and recovery. The funding sources, structure, financial instruments and management arrangements for such a fund may vary depending on the agreed uses of the fund in the context of a mutually agreed responsibilities of local governments. It is assumed that the central government is in a position to identify resources to capitalize such a fund. In a situation when the central government experiences a downward trend in domestic revenues, capitalizing such funds is a challenging but manageable task. Assuming that the government has access to international or bilateral concessional loans or grants (from the World Bank, International Development Corporation, International Monetary Fund or multilateral and bilateral partners, such as the European Investment Bank, for example), a share of these funds may be allocated to local governments subject to an approved COVID-19 local response and recovery plan. The type of funding (and to some extent the structure and managing arrangements) will depend on the type of financial instruments used by the fund, which may include grants, recoverable grants (zero interest loans) and guarantees to different types and sizes of businesses. Depending on the uses, the funding may be more discretionary or more conditional earmarked for specific uses and specific financial instruments. The Fund may thus be a revolving mechanism if it relies on recoverable funds extending beyond the recovery period or a one-time initiative if it relies only (or mostly) on grants. Application of a revolving mechanism will be easier in local governments where some dedicated business or economic development mechanisms (such as local development corporations, local government loan boards, municipal banks, etc.) already exist. In its simplest form, the Local Government Recovery Fund may take the shape of a window in a re-capitalized existing financial mechanism for local governments as just mentioned.

Transforming local government fiscal space

The second area of support refers to changing the composition of local governments’ fiscal space to make it more flexible and therefore more suitable for local government response and recovery. There are four essential features that characterize local government budgets in many African countries as well as in many developing countries in other parts of the world.

The first one is a large share of recurrent finance (primarily for wages and salaries) as compared the share of capital finance (also known as development finance). It varies for different countries and different types of local governments (being in general lower for cities) but at maximum it can reach over 90 percent of the entire local government annual budget (as is the case in Uganda, for example). The second characteristic is domination of conditional (earmarked) finance in relation to discretionary finance. On average, the share of conditional funding is 70-90 percent of the intergovernmental transfers from central (and/or provincial) governments to local governments (depending on the government structure), and this share is approximately the same for all types of local governments, urban and rural. Lastly, local government budgets are characterized by a high degree of reliance on central government transfers and a low proportion of own source revenues. Lastly, given the dependence of local governments on fiscal transfers from the higher levels of government, the share of local governments in the total public sector expenditure generally remains low in developing countries (e.g., below 14 percent in Uganda in comparison to about 40 percent in the OECD countries).

Taken together, these four factors significantly constrain local governments’ fiscal space and their ability to respond to different crises. First of all, many officially assigned functions of local government (even delivery of essential services, such as solid waste management), often remain heavily underfunded in principle. Secondly, considering the high share of recurrent and conditional funding, local governments cannot reallocate funding to address the emerging needs in the context of a crisis, such as COVID-19, and have to lobby the higher levels of government for reallocations resulting in delays and potentially increasing the negative impact of the pandemic.

Of course, the share of the local government in the general government budget is often a contentious issue, often seeing as a zero sum game and a loss of power by the central government. Changing the situation will take years of political advocacy and a lot of political will (to use the Ugandan example again, it will take Ugandan local government another 10 years to reach a modest share of 25 percent of the total general government budget at the currently planned rate of increase). The same is true for local government revenues. Apart from purely technical issues, such as identifying and sealing multiple leakages in local government revenue administration and achieving their full revenue potential (according to different sources, the current level of revenue collection in many local governments is hardly at 30 to 40 percent of the potential, often even less), there is a bigger (and more contentious) political challenge of revenue sharing between local and higher levels of government. Similarly to the issue of the budget share of local governments in general, the revenue sharing issue requires political advocacy and certain legal and regulatory changes necessarily taking time.

But there are actions that can be undertaken in the short term to transform the existing local government budgets to increase the flexibility of its fiscal space without raising additional finance.

Increased discretionary fiscal space using flexible financial instruments such as Operational Expenditure Block Grants (OEBG). An OEBG is a specific type of intergovernmental fiscal transfer that can be a useful and effective vehicle for governments to implement their COVID-19 response strategies. The beauty of an OEBG is that it combines the most effective elements of the discretionary capital grant and the discretionary recurrent grant. The transfer mechanism of the OEBG is similar to that of a capital grant. The resources are not drawn from the recurrent budget for human resources and basic operating expenditures; instead, they are drawn from other funds and use the modality of the development (or capital budget) as appropriate. Once available to local governments, the OEBG can immediately be applied to implement COVID-19 response protocols. In this respect, the OEBG differs from the regular development or capital budget. It has specific criteria and rules. For example, it cannot be used for any expenditure which creates long-term obligations such as new permanent payroll staff or new large infrastructure requiring operation and maintenance. However, it can be used for (temporary) staff costs, goods and services, and small-scale capital items (e.g. medical equipment or motorcycles). In the medium-term, the discretionary fiscal space of local governments should be increased (even if the total resource envelope remains the same) by decreasing the share of conditional/earmarked finance. This change should come with enhanced control and performance measurement—a direction in which many countries have already moved by introducing robust annual performance assessment systems for local governments.

Increased space for development/capital investments. Local governments in many developing countries account for a miniscule share of total public sector investments, which may be as little as 1 percent for some least developed countries. Of course, the share of local investments is many times more, and depending on the importance of the national projects during a particular investment cycle may be as much as one half of the total investment. The problem is that those investments are carried out by central-level ministries and agencies, not by the local governments concerned. Even when local governments are involved in the process of consultations about projects in their territory (which is the case in many countries), their role remains limited and the center plays the upper hand in all decisions about these investments. It is easy (provided the political will is there) to move the funding for local projects under the management of local governments. This move will increase the responsibility of local governments and the scrutiny (including public control) over their operations while at the same time improving the flexibility of investment decisions and facilitating reallocation decisions in case of emergencies.

Improved resilience of local government fiscal space

Resilience of local government fiscal space refers to its capacity to absorb internal and external shocks and ensure a level of resources required for continued uninterrupted delivery of essential services; an increase in certain goods and services (such as provision of additional quarantine facilities during epidemics, for example); and carry out previously unforeseen activities in reponse to such shocks (such as local economic recovery). Resilience of the local government fiscal space is determined by its ability to (1) mitigate the decrease in one type of revenues by quickly switching to other types of revenues; (2) discretionary powers to reallocate funding to different uses within the existing envelope; and (3) raise additional finance by tapping into debt markets and other alternative (nontraditional) finance mechanisms.

Improved resilience of local government fiscal space builds on the approaches already discussed, in particular greater flexibility in terms of the grant nomenclature (especially the share of discretionary funding), increase in own source revenues, and more flexible financial instruments is a very essential contribution to improved resilience. More substantive changes beyond the immediate reallocation of resources within the existing envelope will take more effort and a longer time as mentioned above. Hence, improving the resilience of local government fiscal space involves medium to long term interventions that include policy and regulatory changes.

Speaking about specific approaches and mechanisms, three areas are of particular relevance.

Reserve/emergency accounts for local governments. A reserve or emergency account replenished on an annual basis should serve as a cushion in case of emergencies. This account should be subject to strict regulation to ensure its use for the declared purposes. As in the case of the financial mechanisms previously discussed, there should be a clear link between such an account and local government disaster risk preparedness and management plans. It is important that this dimension is incorporated in the local government planning guidelines and they are appropriately guided on planning and budgeting for disaster risks, including its financial and nonfinancial aspects.

Alternative financing mechanisms for local governments. Subnational pooled financing mechanisms, such as municipal banks, loan boards, and other similar structures, may serve as a source of additional finance in difficult times. Local diaspora finance vehicles offers an opportunity to tap into low-cost finance although establishing such mechanisms is a challenging task and will require the support of the central government and development partners. Local Development Corporations, Municipal Development Funds and such like mechanisms with their own dedicated funding can also absorb and mitigate the shock. Another solution is application of innovative financial instruments for financing local development projects that hedge against various financial and nonfinancial risks (such as the risks of foreign exchange depreciation, implementation delays, natural disasters, etc). Various forms of partnerships with the private sector is one more example of alternative financing approaches. These partnerships may be based on both financial and nonfinancial contributions from the partners and, if properly structured and implemented, will decrease their mutual risks while improving resilience of the investment process.

Enhanced local revenue administration systems. by revising the sources, rates, collection methods, etc. Despite years of multiple efforts by multiple actors, local revenue collection stubbornly remains at a low level. It may be unpopular to speak about local tax and nontax revenues now, at a time of massive relief efforts in response to COVID-19 but this conversation needs to happen sooner rather than later. The present system of revenue administration at the local level suffers from numerous leakages, inefficiencies, multiple exemptions and poor enforcement. The central government should consider revenue sharing schemes that would allow an expanded discretionary fiscal space for local governments as discussed above.

Enhanced digitization of services and public financial management. The COVID-19 crisis has clearly demonstrated the importance of digital systems and digital solutions for local government fiscal space. In and by itself, digitization does not increase the fiscal space but it is a powerful enabler of for more efficient public financial management systems, which eventually reflect on the flexibility and resilience of fiscal space. For example, local governments applying digital solutions for revenue collection has seen a less precipitous drop in OSR. This is partly because of the better control and easiness of tax and non-tax payments but also because this does not require physical contact, which is problematic under COVID-19 restrictions, such as limited freedom of movement and significantly reduced numbers of civil servants physically present in office. Furthermore, digital solutions (online platforms, mobile phone systems, etc.) allow local governments to continue to provide certain services against a fee (such as issuance of permits, certificates, etc.), which also contributes positively to the local government fiscal space.

As development partners, we should be concerned about the allocative efficiency of public funds where the marginal benefit from public goods and services exceeds the marginal cost of their production by the greatest amount. Local governments are well positioned to provide the best allocative efficiency although the challenges, particularly in the developing world, remain overwhelming. Our contribution to further strengthening the capacity of local governments to deliver maximum public benefit at minimum cost will help our partner governments to improve the quality and quantity of services and will improve the lives of the people in those countries. But it will also help us achieve better value for money for our development funding. We should all be advocates of local government at this time. This is one of the lessons we have learned from COVID-19 and, hopefully, part of the new normal.