It is always a pleasant surprise when your research comes with unexpected results. Getting confirmation of your ideas is somewhat boring but unexpected results challenge you intellectually, prompting a revision of your approach in search of new explanations.

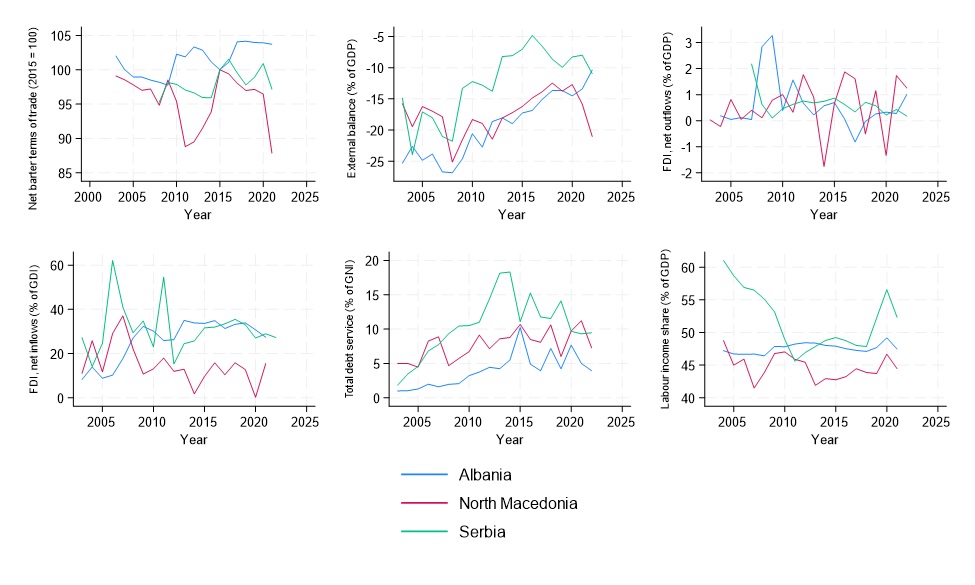

This is what happened with the research Boris Kagarlitsky and I have recently presented at an international seminar on comparative economics at Belgrade University. The research is about the impact of foreign direct investments on the economic dependency of the Western Balkans (more specifically, three countries that make up the Open Balkan – Albania, North Macedonia, and Serbia). We take a Marxist explanatory paradigm and treat these countries as peripheral in relation to the European Union (the so-called EU 15). In doing so, we use a number of dependency indicators (e.g., terms of trade, external balance and others) to investigate the impact of the FDI inflows and stocks. Mainstream economics hails FDI as an important source of finance for development. Our study did not find any positive impact of FDI on indicators of dependency. On the contrary, it highlighted the negative impact of FDI on the external balance (FDI reduces the external balance), FDI outflows (FDI increases FDI outflows), and domestic investment (FDI displaces domestic investment). At the same time, the research did not find any positive impact on the other indicators of dependency.

These were the findings we expected. What we did not expect was the negative correlation between control of corruption and dependency (control of corruption was used as a control variable in our research). In other words, better control of corruption results not in the improvement but in the deterioration of dependency. Specifically, better control of corruption is negatively correlated with the terms of trade and external balance of the periphery countries. Our initial assumption was that improved governance (measured by control of corruption) reflects greater domestic development agency, which should lead to more effective and efficient development interventions and, hence, less dependency. Apparently, this is not the case.

This goes against the prevailing view in mainstream economics, which links more development with less corruption. There have been more recently some heterodox views on the relationship between corruption and development, claiming that corruption may have a positive impact on development, particularly in an inefficient institutional setting by greasing the wheels of commerce in the presence of weak regulatory frameworks. Yuen Yuen Ang in her “How China Escaped the Poverty Trap” famously praised the positive impact of corruption on China’s development, first in the form of “speed money” (payments to bypass red tape and speed up administrative processes) and then as “access money” in the form of future benefits resulting from profitable partnerships with the private sector (e.g., a new urban development project where government officials have a stake). In Ang’s words, “Working hand-in-hand with businesses ensured continued growth for the country, while elite officeholders along with their capitalist partners could harvest the cream of prosperity.”

Our research did not look into the relationship between corruption and economic growth, which was the focus of the other studies, nor did it look into the relationship between corruption and FDI. In fact, even the relationship between corruption and dependency (which emerged in our research) was not a research objective. But once it was there, we started looking for an explanation.

The most obvious explanation is that better control of corruption does not necessarily translate into “better” FDI that reduces a country’s economic dependency. The FDI policy is usually grounded in longer-term strategies, unaffected by short-term fluctuations in governance performance. If a government considers economic dependency a non-issue and does not strive for greater economic independence, then its level of corruption will not affect its dependency, even if FDI is implemented more efficiently and the economic loss is reduced.

But there is another explanation, which links dependency, FDI and corruption. The positive relationship between dependency and corruption becomes less of an enigma when the impact of control of corruption on FDI is taken into account. Mainstream economics insists on a negative impact of corruption on FDI inflows. One IMF paper claims that corruption acts as a tax on FDI, and one percent increase in the tax rate reduces FDI by 5%. Reduced corruption (better control of corruption) would then operate as a tax incentive. If this reasoning is accepted, then better control of corruption invites more FDI and because FDI produces a negative impact on dependency (as our research finds), better control of corruption implies worse results in terms of economic dependency. In other words, control of corruption operates in this case as an intervening variable.

Let me now move to the prison part of this post. Working on this research has been a unique experience for me because my co-author, Boris Kagarlitsky, is now in a Russian prison. He was sentenced by a military court to 5 years for justifying terrorism because of his position on the war in Ukraine. Over the years and decades, Boris produced a very fine Marxist analysis of the dependency theory in Russia and globally. I highly recommend two of his books (both available in English): “From Empires to Imperialism” and “Empire and the World Periphery”. Before his arrest, he was a Professor at the Moscow Higher School of Economics, which used to be a leading (and most positively liberal) school of economics in Russia. As befits a true Marxist, Boris has always been a political activist. He was first arrested and imprisoned for his political activism under Brezhnev. The subsequent “democratic” Russian governments did not treat him any better: he was arrested under Yeltsin and Putin before his imprisonment early this year.

To be able to communicate with Boris, I had to learn how to use the prison mail system managed by the Russian Federal Correctional Service. The system is of course a great improvement over the Stalinist Gulag when an exchange of letters between prisoners and their families could take many months (if it was at all possible). Nowadays you can send your message online for a modest fee, and your addressee will compose a handwritten letter, which will then be scanned and sent to you electronically. Oh, you have to pay for the reply as well, if you want a reply. And you can write in Russian only because, I guess, the prison censors are not very fluent in other languages. On the positive side, you can also attach a picture to your letter to prison, a useful feature I used to share with Boris charts and statistics for our research. But if your addressee has been sent to another prison (as happened to Boris during our work), your letter won’t be forwarded, it will be returned to you (no reimbursement). You will then need to wait for information about the new facility to make another attempt. Needless to say, this makes collaboration on a research project very challenging.

Not once did Boris complain about his condition although he is currently in a cramped prison cell together with nine other people. He diligently responded to all my questions, regularly providing his thoughtful contributions. I admire his perseverance and dedication. This blog post is a tribute to Boris and a reminder about him and other political prisoners in Russia.